I never thought Prince George would hold such fascinating historical secrets. The city always seemed too quiet, too ordinary for anything truly intriguing to be hiding beneath its familiar streets. That all changed when I visited the Nelson Museum and discovered something unexpected – this northern city might have played a significant role in Cold War defense planning.

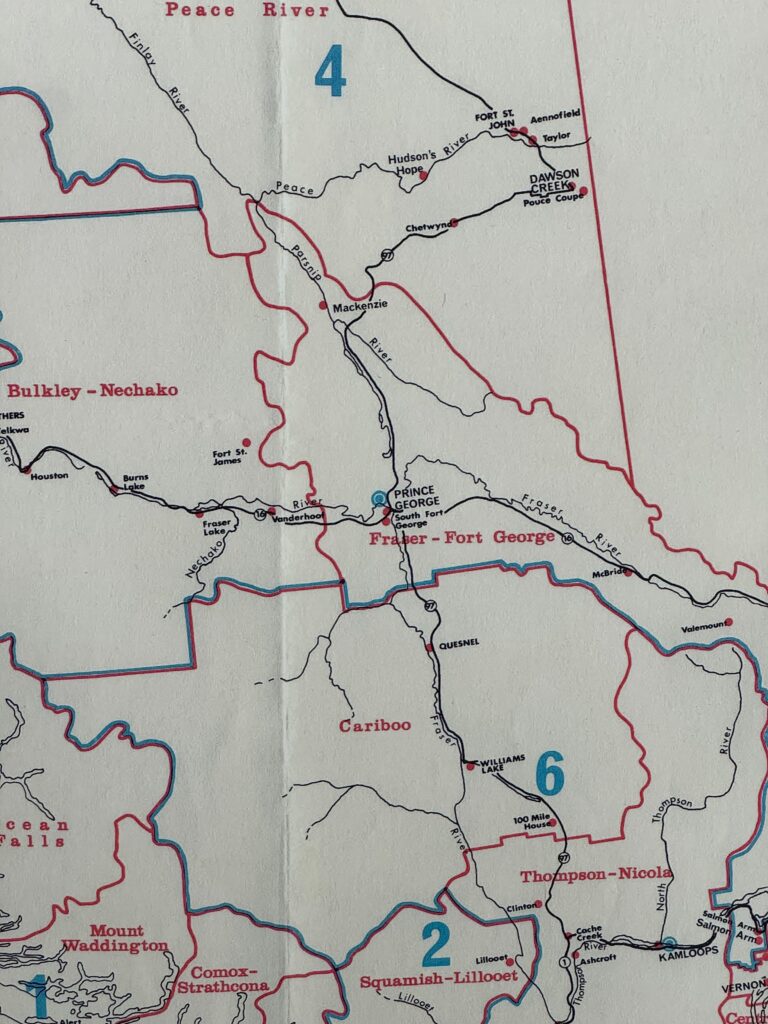

During my visit to Nelson’s Cold War bunker, I stumbled upon a fascinating map that sparked my curiosity. The map detailed various Zone Emergency Government Headquarters (ZEGHQs) across B.C., with Prince George designated as the Northern Zone HQ. This discovery led me down a path of research into our city’s Cold War preparations, revealing a complex network of emergency planning that extended throughout the province.

My research into Prince George’s Cold War infrastructure has proven challenging, with the only concrete reference being a facility designation found on a map created by Andrew Burtch. The challenge in uncovering its history lies in the scarcity of official documentation and verifiable information. Like many aspects of Cold War infrastructure, concrete information about which facilities were actually constructed remains elusive.

The broader context becomes clearer when examining similar structures across B.C. In Lone Butte, for instance, a tiny concrete bunker still stands as a testament to this era. Unlike the larger government headquarters, this smaller bunker was designed for the local postmaster to conduct radiation monitoring in case of nuclear attack. These varying scales of Cold War infrastructure – from major regional headquarters to local monitoring stations – paint a picture of how comprehensive civil defense planning was during this period.

What makes Prince George’s potential bunker particularly interesting is the strategic thinking behind its location. While the city served as a key transportation hub and regional center, it was specifically chosen as a “non-target” area. Unlike major urban centers that might be primary targets in a nuclear attack, Prince George’s relative isolation made it an ideal location for emergency operations. The bunkers of this era weren’t designed to withstand direct nuclear strikes, but rather to provide safe locations for continuing government operations in less-targeted areas.

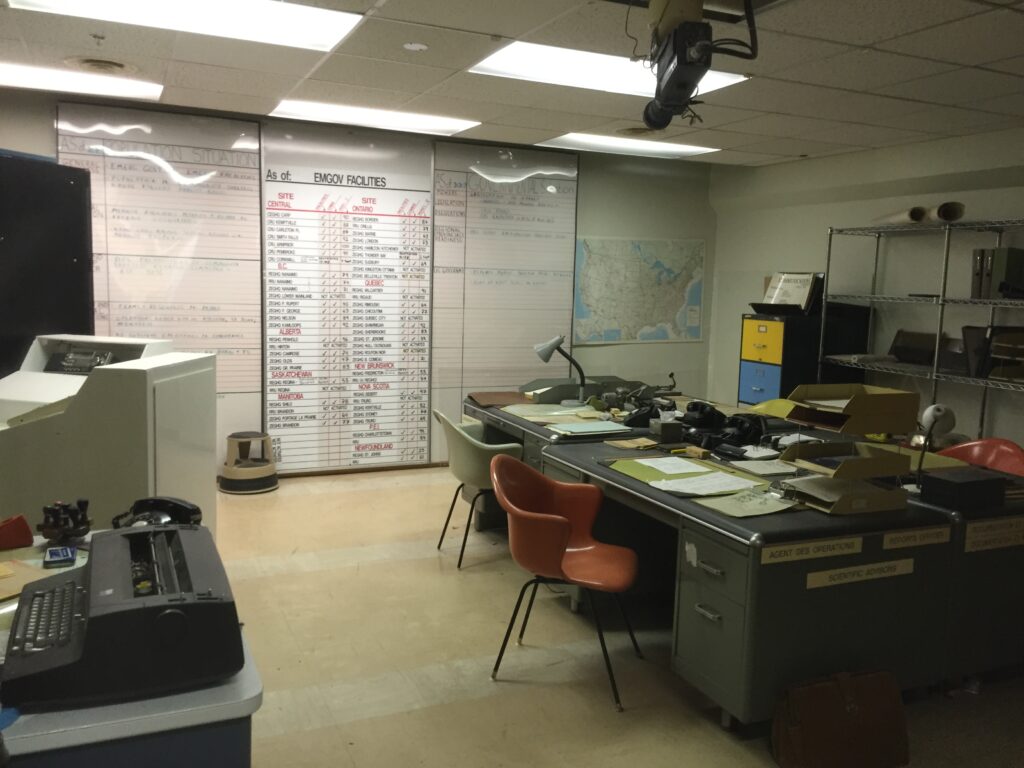

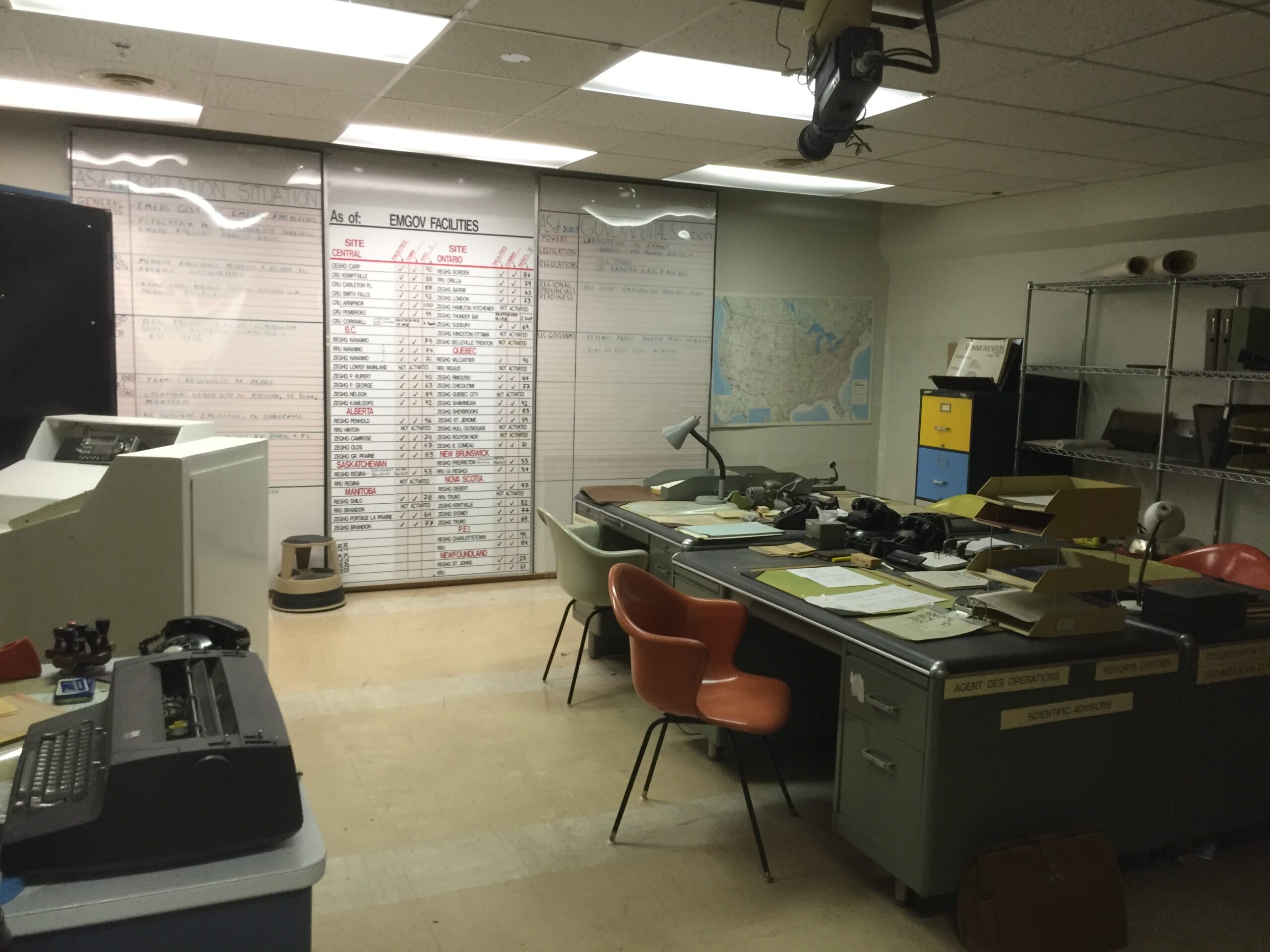

The image of the status board from the Diefenbunker in Ontario, where the Prime Minister would have been stationed, gives us a glimpse into how these facilities were meant to operate on a national scale. The interconnected nature of Canada’s emergency response network linked facilities across the country, from the highest levels of government down to local monitoring stations.

Following the Clues

Based on my analysis of historical maps, if the marked location is accurate, the bunker site would likely be somewhere north of the Nechako River, between the Hart Highway and Miworth. However, I’ve learned that these maps were often drawn for representation rather than precise accuracy.

Several possibilities have emerged in my investigation:

The Prince George Post Office seems a likely candidate, following the pattern seen in other communities like Nelson where postal facilities played crucial roles in civil defense. City Hall or other government administrative buildings might also have housed such facilities. Given Prince George’s importance as a transportation hub, the bunker might have been integrated near railway or other critical infrastructure.

The Search Continues

My investigation isn’t over. I’ve submitted a freedom of information request to the city regarding building permits for government structures from that era and any information about bunkers built in Prince George. I’m also working to establish contact with Public Safety Canada, the organization that superseded earlier Emergency Management Organizations in Canada.

The image of the status board from the Diefenbunker in Ontario, where the Prime Minister would have been stationed, gives us a glimpse into how these facilities were meant to operate on a national scale. The interconnected nature of Canada’s emergency response network linked facilities across the country, from the highest levels of government down to local monitoring stations.

The search continues for more concrete evidence about our city’s Cold War bunker. If you have any information that might help solve this historical mystery, please contact ote@unbc.ca.