Why We Observe Remembrance Day

Since the end of the First World War, Canadians and other Commonwealth citizens have marked Remembrance Day as a memorial day to honour all those who have fought and died for our freedom. On November 11 of each year, Canadians pause for a minute of silence to honour and remember the more than 2 million Canadians who have served and continue to serve their country during times of war, conflict, and peace. This moment of silence is known as Remembrance Day. If we do not remember, their sacrifice is meaningless.

A Brief History of Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day was first celebrated in the British Commonwealth in 1919. This is a tradition started by King George V to remember the soldiers who died during the conflict. It was originally called Armistice Day to remember the armistice that ended the First World War on November 11, 1918, at 11 a.m. Armistice Day was celebrated on the Monday of the week that November 11 fell in until 1930. In 1928, a group of prominent citizens, many of whom were war veterans, advocated for a greater degree of acknowledgment as well as the separation of the remembrance of wartime sacrifice from the Thanksgiving holiday. Thanksgiving Day was relocated in 1931 in order to make room for the newly titled Remembrance Day, which would be honoured on November 11. Instead of focusing on the political and military developments that led to victory in the First World War, the remembrance of soldiers who died would be the primary focus of Remembrance Day.

How People Observe Remembrance Day

On November 11, the official Canadian national ceremonies take place at the National War Memorial in Ottawa, ON. The Governor General is in charge of the ceremony, which follows a strict set of rules. Other services are held all over Canada. They often include the playing of “The Last Post,” the reading of “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae, and two minutes of silence at 11:00.

Symbols of Remembrance Day

Because of the poem “In Flanders Fields” by Canadian doctor Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, the poppy is the most well-known symbol of Remembrance Day. People used to wear real poppies, but now most people wear fake ones. Their bright red colour became a sign of the blood shed in wars. As a further gesture of remembrance for those who served in the military and gave their lives in defence of their country, Canada is home to a number of war cemeteries. We honour the freedom that these brave Canadians fought for by commemorating their service and sacrifice. We must remember.

Remembering Soldiers of Colour

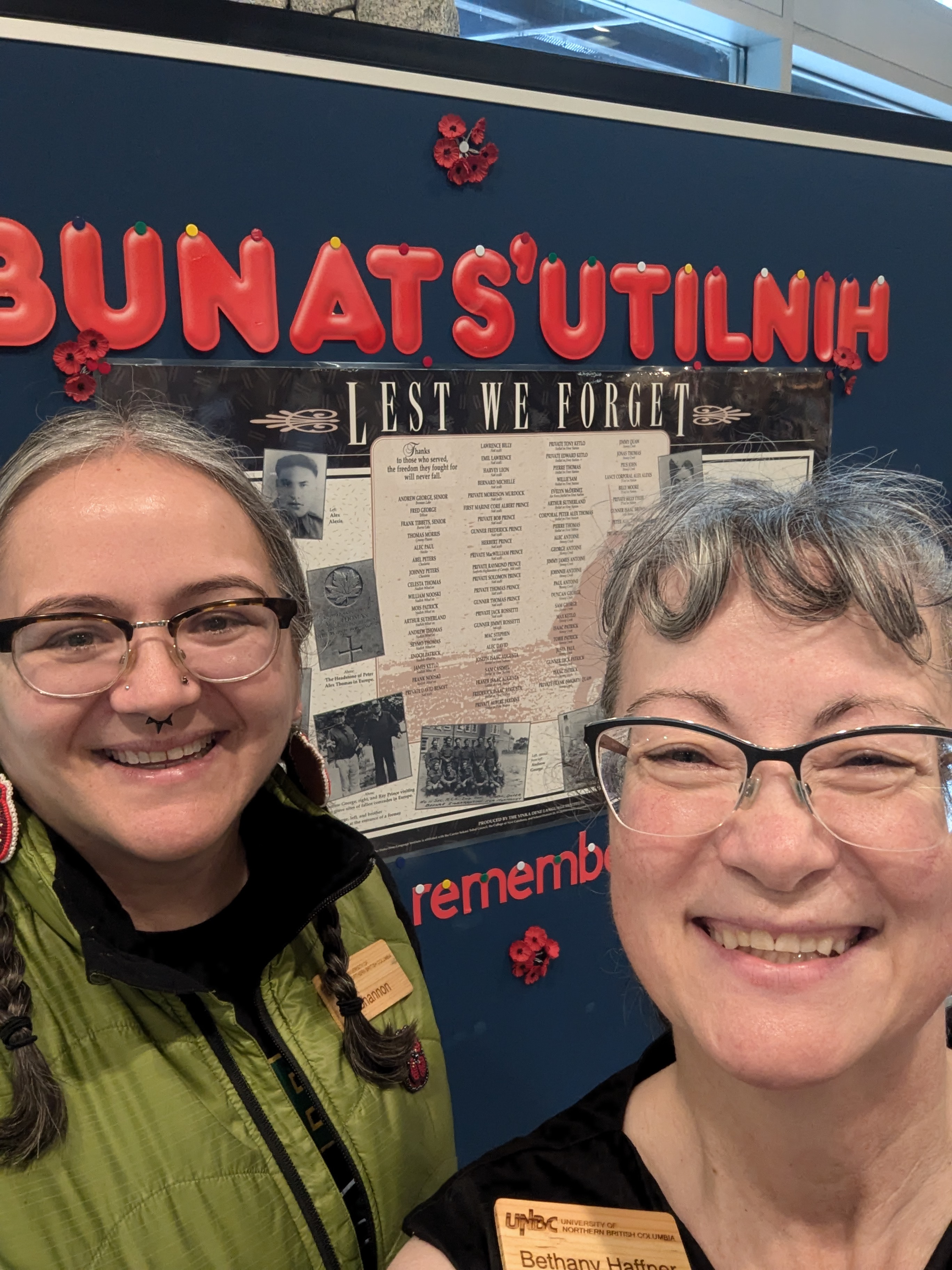

“Remembering soldiers of colour” is not something that pops up in your feed very frequently at all. The story and visuals of Remembrance Day (and both world wars) tend to centre on the experience of white Europeans, and we forget that people of colour also served in these wars. Let us honour their sacrifices and convey a fuller, more complex story of the World Wars for this Remembrance Day and every year thereafter.

“Before I knew how much the Indians had contributed, growing up I thought it was very much a white war..We weren’t taught about the Indians in school.” Quote from Dr. Irfan Malik.

WWI & Soldiers of Colour

“The role played by the four million non-white non-Europeans who fought and laboured on the western front [during World Conflict I], as well as in other theatres of the war in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, has been erased from popular memory.” -David Olusoga, The Guardian. European nations depended on their colonies for soldiers and workers during World War I, highlighting the role colonialism played in the war. For instance, when France gathered its army from Senegal, North Africa, Vietnam, and Madagascar, Britain used troops from India, Africa, and the Caribbean. Even Germany resorted to the use of religion as a weapon in an effort to win the allegiance of the Ottoman Empire and the rulers of other Muslim countries in order to fight in armed confrontation against Britain, France, and Russia.

What we don’t remember

It’s not only that we forget about people of colour who served in the military; it’s also that their experiences during and after the wars were shaped by the fact that they weren’t white. This is something we tend to overlook. For instance, during both world wars, the vast majority of those promoted to higher positions and awarded medals were white soldiers from Western countries. In addition, the French had the discriminatory assumption that West African soldiers “could better tolerate the shock of war and experienced less intense physical pain.” This justified their use as shock soldiers… As a result, West African soldiers on the Western Front between 1917 and 1918 were twice as likely as white French infantrymen to be killed in action.” Despite the fact that they had served their country throughout the war, black British troops and labourers who worked in industries were subjected to violence by white mobs after the war ended.

“Britain didn’t fight the Second World War, the British Empire did.” – Yasmin Khan, Historian at Oxford University & Author of “The Raj at War.

Highlighting contributions of soldiers of colour

To show you the significant sacrifices made by soldiers of colour, here I’ll present some data that I learned from my favourite instagram page (@Oncanadaproject): There were 3.8 million Indian soldiers who participated in World War I and World War II. While 6,300 Indian soldiers were awarded for valour, only 31 were awarded the Victoria Cross.

The British West Indies Regiment (BWIR), comprised of 16,000 Caribbean soldiers, was established in 1915. There were 81 medals awarded to BWIR members before the end of WWI. The BWIR consisted of men from Jamaica to the Bahamas.

In World War II, more than a million African soldiers served. Also during this time , 80,000 african labourers worked to construct ships out of uranium, steel, and platinum.

According to the available data, more than forty percent of the military troops who served the British Empire during World War II came from non-Western countries that were a part of the Commonwealth.

NEXT STEPS

This Remembrance Day – and those that follow – let’s remember the contributions of soldiers of colour and tell a more complex and complete story of the world wars. I invite you to s pend some time investigating resources that document the experiences of people of colour in the armed forces, such as:

- Library of Birmingham’s Stories of OmissioncCo Exploring the West Indian contribution to the First World War by Gateways to the First World War • The research of Dr Irfan Malik and David Olusoga

When you read or watch news about Remembrance Day, ask yourself: Whose stories are being told? Try to be aware of the emphasis placed on the ethnicity or nationality of the soldiers. Are Indigenous, Black, Japanese, and other BIPOC soldiers’ contributions and involvement being tokenized?

Let’s REMEMBER EVERYONE ON REMEMBRANCE DAY from now on. Lest we forget.