Before coming to UNBC, I’d never heard of Indigenous Veterans Day. As I was walking by the student hallway one day in early November, I noticed a display in the Doug Little Lounge at UNBC, that made me stop and learn more about what it was about.

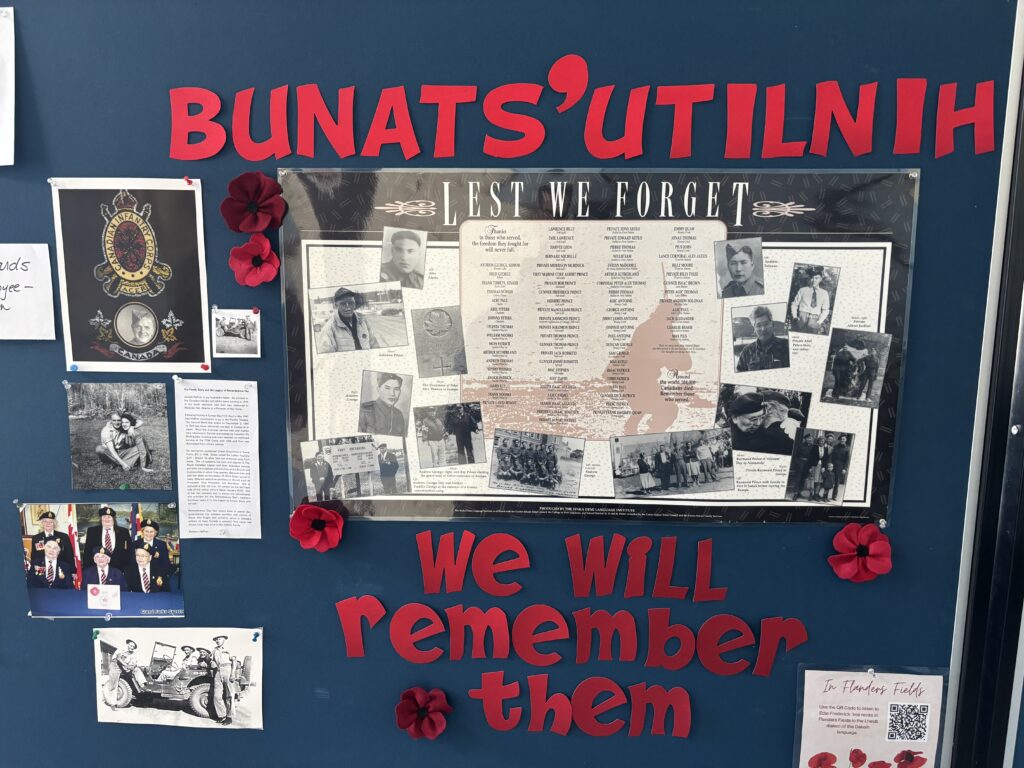

Indigenous Veterans Day happens every November 8, three days before Remembrance Day. It started in Winnipeg in 1994 because Indigenous veterans weren’t being recognized in regular Remembrance Day ceremonies. Over 12,000 Indigenous people served in WWI, WWII, and the Korean War, but their stories were basically invisible.

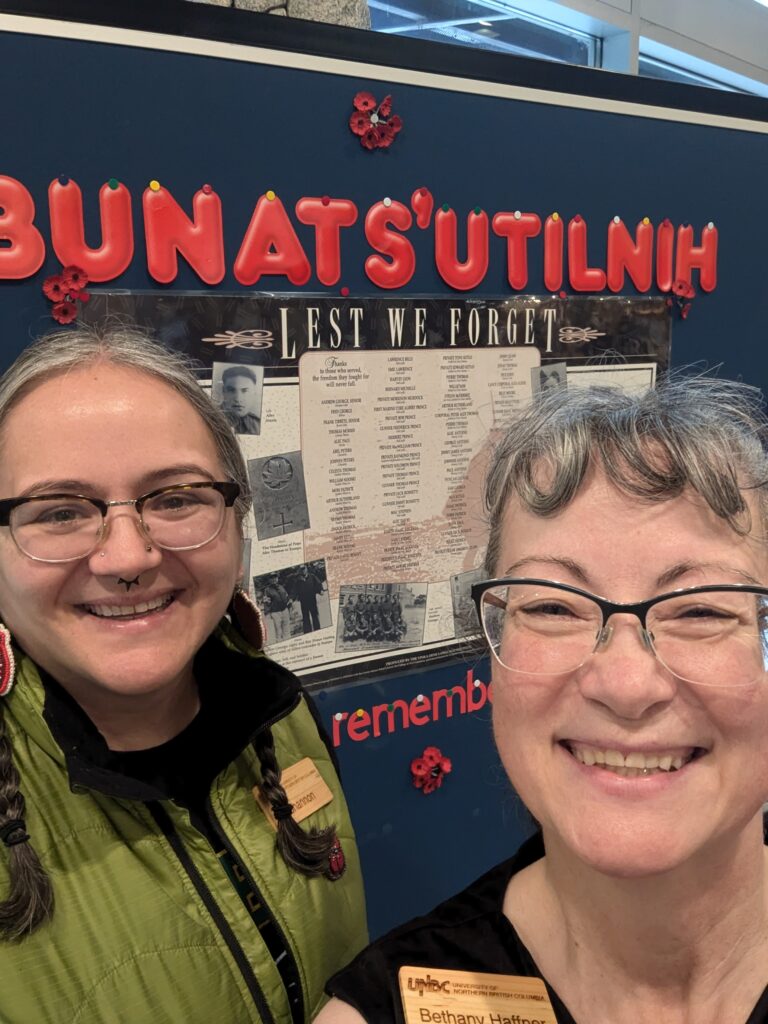

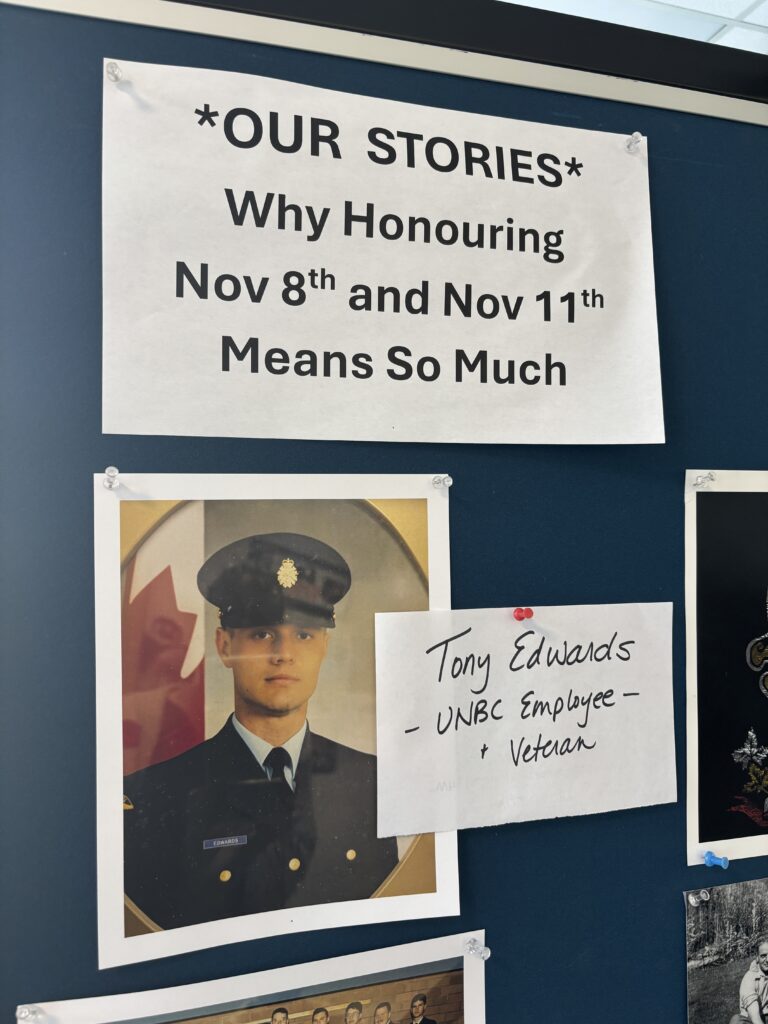

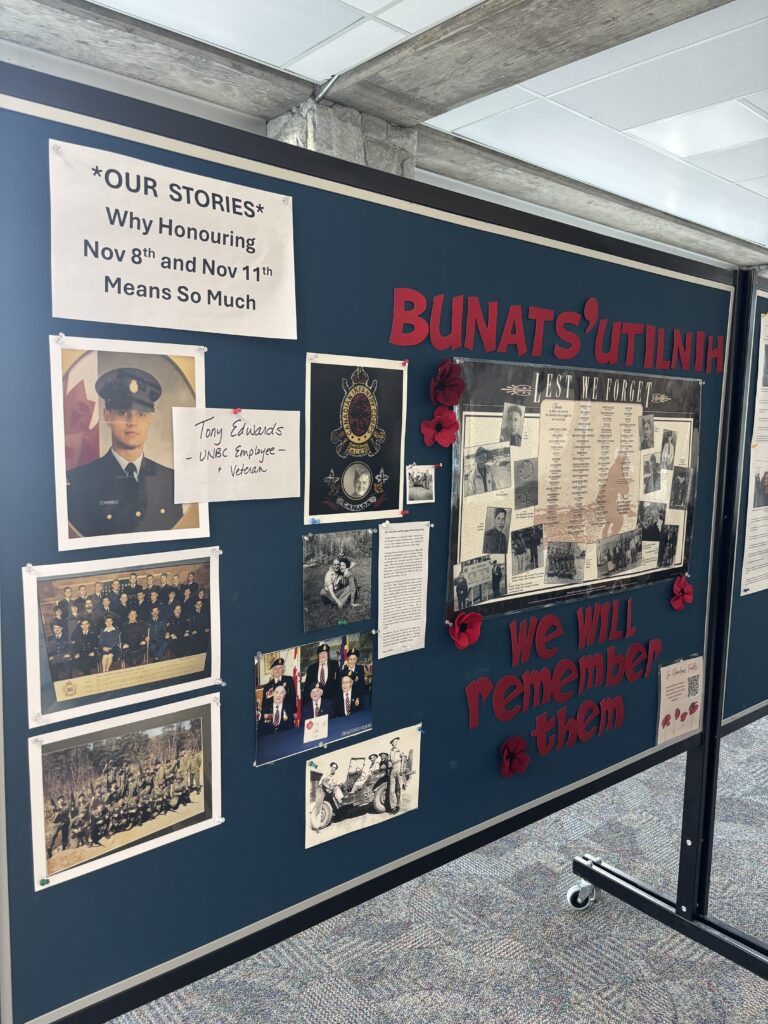

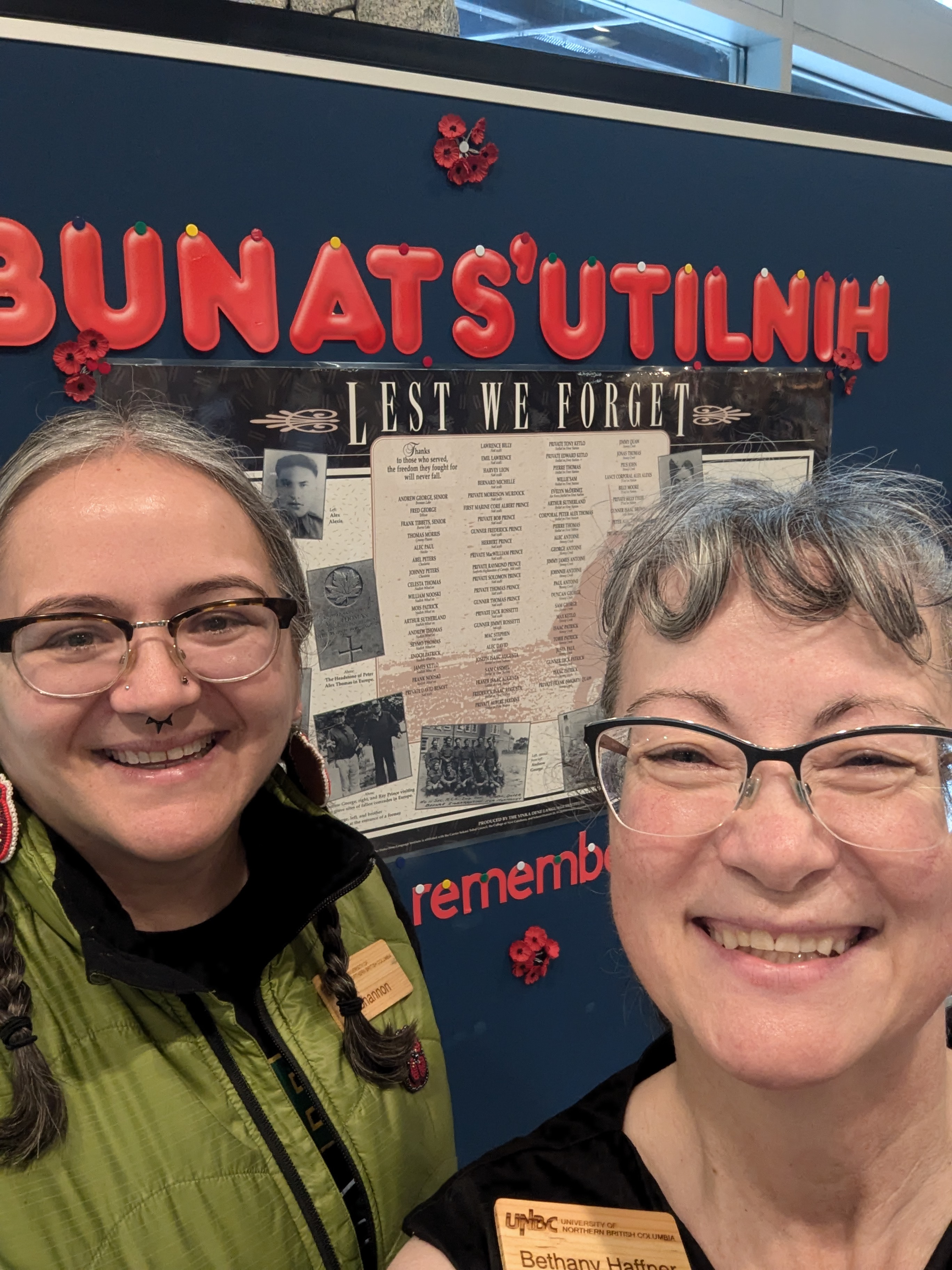

Shannon MacKay, UNBC’s Indigenous Cultural Connections Coordinator, and Bethany Haffner, UNBC staff member, put together the “UNBC Remembers” display. What caught my attention was how personal it was. Haffner’s father-in-law served in WWII, and there was a UNBC employee named Tony Edwards who’s also a veteran.

The display had CBC articles explaining how Indigenous veterans got treated after they came home. A lot of them lost their Indian status just for enlisting. It took until 1995 – fifty years after WWII ended – for Indigenous people to even be allowed to lay wreaths at the National War Memorial. The government didn’t give First Nations veterans the same benefits as other veterans until 2003.

One veteran, David Ward, spent time living on the streets in Ottawa after serving. While he was at the National War Memorial one day in the 90s, he saw ceremonies for other countries and thought, “We don’t have a day for us. Why shouldn’t we?” That’s how the push for Indigenous Veterans Day started.

The hardest part? Finding all the Indigenous veterans. Many enlisted under “white names” to avoid discrimination, and the Department of Indian Affairs took their military records and buried them in their own files. People are still trying to track down who actually served.

The display explained that Indigenous people weren’t considered citizens and couldn’t be drafted, but many volunteered anyway despite having to travel from remote communities and learn English. They couldn’t join the Air Force until 1942 or the Navy until 1943.

Walking past that display made me realize how much I didn’t know. Indigenous Veterans Day isn’t just about honoring service – it’s about recognizing people who fought for a country that didn’t even consider them citizens at the time.

I reached out to Bethany Haffner to see if she wanted to share any pictures or additional comments with Over The Edge readers.

“I’m so glad the Indigenous Veterans Day & Remembrance Day display has made a difference. Each of us can honour those who served, and who are currently serving, by taking time to pause and ask ourselves what sacrifices they made for our benefit and for the peace that we live in. For the Indigenous soldiers the sacrifice was more than their life, it was also their community and their status. By remembering together we can acknowledge, push for change, and honour the Indigenous Veterans and current military service men and women who so bravely serve so that we can live peacefully.”

Bethany Haffner