Saint Jerome (Cutting from the Murano Gradual)

Sorry about the title. Unlike most of the paintings that I discuss in this column, this particular masterpiece was found in a book rather than on a wall. I mean, it’s probably on a wall now, but that’s only because somebody decided to cut it out of the book. Imagine having that nerve – discovering a priceless illuminated manuscript and reaching for a pair of scissors as if culture is just one big scrapbooking party. (They say that you should believe in yourself, but they clearly aren’t thinking of the guy who cuts up illuminated manuscripts when they say that.)

This scene portrays Saint Jerome and a lion. The lion looks grouchy, St. J. looks well-fed and the priest in the background looks concerned about the fact that there’s a lion in this painting. No doubt he would be more at his ease if Saint Jerome was giving a pedicure to a different sort of animal. Perhaps a lemming. Maybe an ostrich. Lions simply don’t have the right reputation to be hanging out with Dalmatian (Inferring that he was born in the Roman province of Dalmatia and not, as I first supposed, that he was spotted and lived with firefighters.) theologians getting their nails done.

A little more research informs us that the lion had a thorn in his paw and Jerome is seen here removing the offending object. (Imagine how life was for lions before Dalmatian theologians became a thing. No doubt they had to chew the thorns out of their own paws like peasants. I’ll wager you’ve never once thought about that, have you?) It also turns out that the Saint was almost always portrayed in the company of this particular lion, so clearly the operation went well. It has been suggested that the priest in the background is arriving with some sort of ointment with which to aid Saint Jerome’s treatment of the lion. I cannot offer an opinion on this one way or the other – it seems a reasonable claim but if you told me that he was simply hungry and had brought his priestly lunch, I’d find that equally credible.

The artist who produced this painting is known as the Master of the Murano Gradual. This tells us nothing about the artist whatsoever except that they were much involved in the production of this particular gradual from Murano. (A sort of suburb of Venice. Everybody gets about on bridges.) Whoever did this was clearly quite practiced at the art of taking thin bits of gold and gobs of egg yolk and turning them into pictures of disgruntled lions. You’d think that this information would narrow down the list quite a bit, but no; that appears to have been all that people in Murano did back in the day.

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably wondering “What’s on the back?” because usually if you cut a picture out of a book, there’s bound to be something written on the back. Just goes to show what you and I know. There’s nothing on the back at all. It’s plain as rice.

A Woman with a Dog

I would tell you about the subject of this piece, but I’m afraid that its title has done rather a complete job of that for me.

This painting is by one Jean Honoré Fragonard, who made a lot of effort to be impressive as a painter only to be largely ignored during his own lifetime. Perhaps one of the reasons that he was a flop was that he always forgot to put dates on his works. People can forgive a lot, but that’s just the sort of negligence that leads to you getting snubbed into a lonely death. A Woman with a Dog, for example, is believed to have been painted around 1769, but who knows? You might buy it on that understanding only to discover that its actual creation had been in 1770 or even 1767 and then what a sucker you’d look.

A Woman with a Dog is part of a series of paintings by Fragonard known as his Fantasy Figures. I’ve gone over them and they seem a charming set of character studies. The women are almost all strikingly pretty and the men are almost all shockingly plain, and I don’t know if that observation says more about Fragonard or myself.

Probably the most unsettling image in all the Fantasy Figures is the dog in this painting. If you look closely, you’ll see that he’s a perfect lookalike for Pennywise the Dancing Clown. Some people have suggested that there is supposed to be a witty contrast in this image between the larger-than-life image of the woman with her oversized pearls, outrageous collar and full chin and the diminutive size of her beloved animal. These persons have not seen Bill Skarsgård’s 2017 performance and it shows. The real contrast in this image is between the woman’s wide-eyed innocence and the outlandish depravity of her pet.

Just look at that animal’s eyes and tell me I’m wrong.

Liberty or Death

This highly symbolic painting portrays the Genius of France between Liberty and Death. For context, it was painted right at the end of the Reign of Terror, when just about every idealist had had a go at executing people who disagreed with them, before inevitably being executed in turn. As such, while we might be inclined to believe that the Genius is simply describing the state of affairs as he sees them, it is not unreasonable to think that he is actually offering a threatening ultimatum very common at the time. We are invited to side with Liberty as embodied by the French Republic, or else. (Precisely the kind of viewpoint that leads one to start admiring the extraordinary potential of a good guillotine.)

The artist, Jean-Baptiste Regnault, has portrayed Liberty as being positively cluttered with iconography. Her cloud strains under the weight of the various objets d’art that are intended to leave us no doubt that “Liberty” and “The First Republic” are synonymous. Even Genius has the revolutionary colours showing among the feathers of his wings.

By contrast, Death is far less encumbered. He has a hero’s wreath and his traditional instrument of harvest, and that’s it (Precisely the kind of viewpoint that leads one to start admiring the extraordinary potential of a good guillotine.) His attitude is much more that of someone who, when invited to discuss his trade, simply shrugs and says, “You know, people die. Whatever.”

Probably my favourite aspects of this painting are the expressions on everyone’s faces.

Liberty looks brutally unimpressed. The sarcastic thoughts going through her head as she holds her square and Phrygian cap aloft make it hard to take her all that seriously. She’s like “Genius! Get the hell back here! You forgot your scarlet cap of liberty again!”(Because that’s what he needs right now. Not the scarlet loincloth of liberty. No. The cap.)

Genius, meanwhile, has the expression of someone who thinks he’s a genius because he just realized that if doors had never been invented, knock-knock jokes wouldn’t be popular at all… because he’s stoned out of his skull.

Death’s expression: “Hey.”

The Dissolute Household

If you ever want to feel better about how messy your home is, spend some time perusing the catalogue of iconic Dutch artist Jan Steen. He makes domestic mismanagement the cautionary subject of many of his paintings.(A number of commentaries have suggested that the name Jan Steen is a household byward in the Netherlands, used to denote a messy or disorganized home. I asked a Dutch friend of mine if he was familiar with this and he was not. Bullshit is everywhere – everywhere you look, lo, there is the shit of bulls.)

In this painting, dating from the early ‘60s, (The 1660s. Like the 1960s, but completely different.) Steen can be seen sitting in the centre of the room, filling the role of the delinquent man of this chaotic house. This isn’t the only time Steen saw fit to put himself in one of his paintings. It seems that he had quite a self-deprecating sense of humour, as he almost always portrays himself as ugly and disreputable.

As we examine this work, we’re supposed to understand that this family is not everything it ought to be. Note the presence of drunkenness, tobacco, disorderly children, infidelity (man of the house flirting with the maid),(Steen didn’t seem to understand that people will not be able to unsee some of the ways in which he portrays himself. I’ll bet that bit him in the ass socially.) irreligiosity (woman’s feet resting on Bible), (It’s generally assumed that this is the Bible. It’s not marked, which means it could theoretically be anything I suppose. Maybe this is actually showing us how the household disrespected Stephen King.) neglect of nobler pastimes (disused lute and backgammon board) and disregard for the poor (unwelcomed beggar at door). Also, they have a cat in the house, which is just perverse.

If you’re looking at this painting and you’re thinking “Have I seen another Jan Steen very much like this?” then you’re a nerd and nobody likes spending time with you, not even your mother. You’re also probably right. There’s another painting, called Beware of Luxury (In English. Presently displayed in Austria as something completely different. Why do we do this? Do you know how many paintings you know by one title that aren’t called that in other languages?) that was painted in the same year as this that contains an almost identical message of warning for the dissipated. Most notably, it has the same basket of goodies hanging over the proceedings. That basket, a gesture of heavy-handed symbolism, preaches a veritable sermon of consequences upon those whose lives are filthy with loose and undisciplined living.

In both The Dissolute Household and Beware of Luxury (and many other Jan Steens) there is prominently displayed a half-peeled lemon. What the hell that means, I’ve no idea. (Perhaps I should leave half-peeled lemons out in front of Dutch people and see if their reactions are in any way enlightening.)

Letter Board

Samuel van Hoogstraten produced a number of paintings like this. Just a bunch of bric-a-brac on a letter board. The apparent mundanity of the objects being portrayed is juxtaposed against the remarkable quality of this near-photorealistic still life. Apparently it was a personal mission in the life of this artist to create two-dimensional images that could fool the viewer into thinking that the subject is present in three dimensions. He was so enthusiastic in his pursuit of these deceptions that he would make little paintings of various household items and place them strategically around his home so that visitors would frequently go to interact with an object only to discover how bloody funny their host was. Examples of this include fish hung on the wall, fruit in the dish rack and a shoe or slipper placed in the corner of a room or under a chair.

There has long been a body of thought that views the letter boards of Van Hoogstraten as rather vain self-portraits. In most of them you will find all manner of references to what a sophisticated fellow he viewed himself. In this one you can see a couple of plays that he wrote, a number of references to the fact that he’s a man of letters and endless references to his being well-groomed. Additionally, there is a medallion that had been gifted to him by some Habsburg or another who had been tricked by one of Van Hoogstraten’s trompe l’oeil paintings and thought that this feat was worth a medal.

Apparently, once he was done creating a painting in which a melee of success indicators were tossed together in a manner as nonchalant as it was meticulous, Van Hoogstraten would then send it as a gift to socially influential people.

In case anybody was looking for evidence of time travel, we have here a very clear example of a 21st century Instagram lifestyle influencer operating in the mid-17th century.

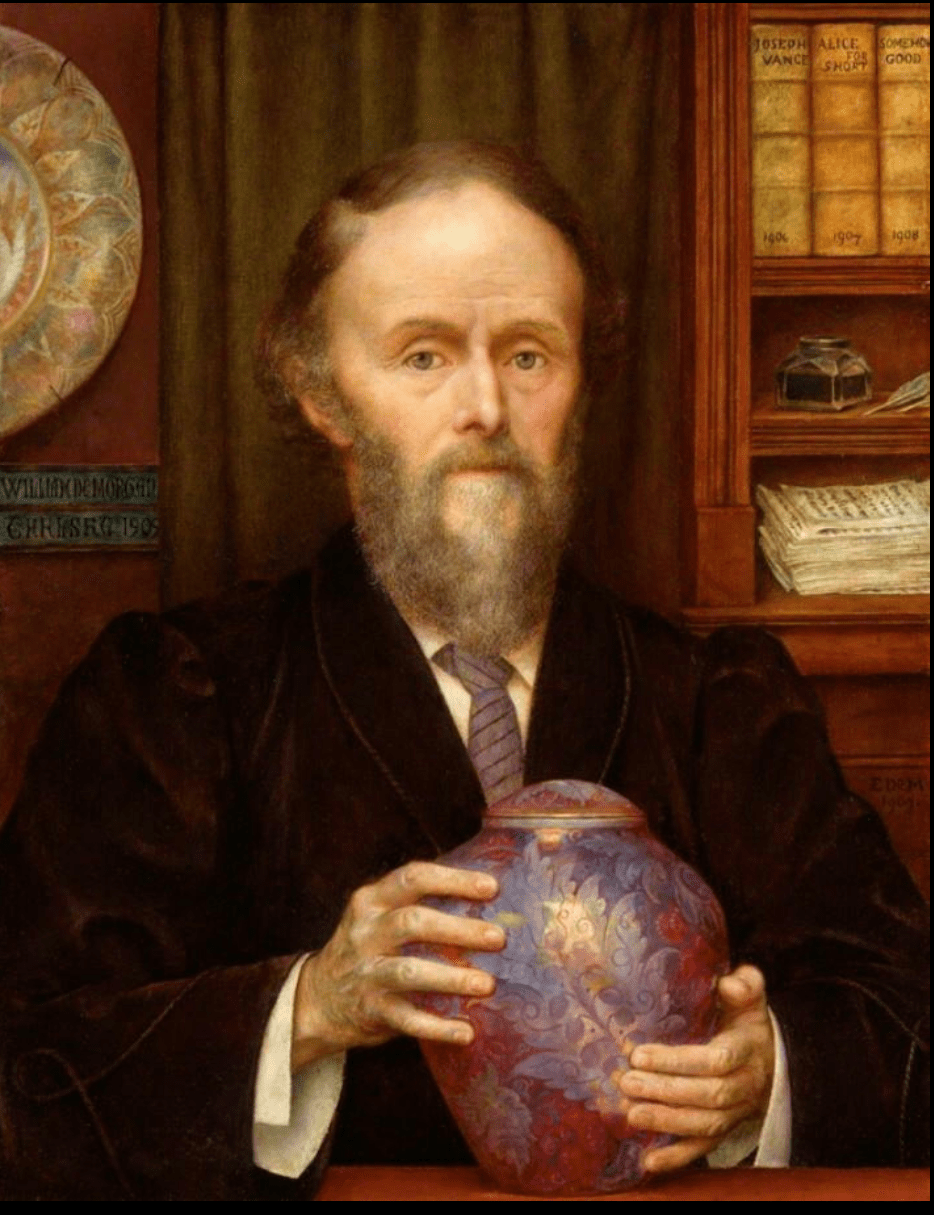

Portrait of William de Morgan Holding Lustre Vase

As someone who often finds paintings, thinks “heh, that’s funny” and then researches them as much as possible, I would like to share a particularly bitter truth of my trade: The more you know about a painting, the less funny it seems. I will illustrate the point by discussing this portrait by Pre-Raphaelite Evelyn de Morgan of her husband, William.

My first impression upon seeing this image was “Aha! De Morgan has painted her husband clutching the urn she has promised he’ll wind up in if he ever again uses the phrase “probably good enough” to describe one of her paintings.”

And that struck me as funny.

What possible reason would there be for a man to be illustrated clutching an urn?

Well, perhaps if I knew the first thing about the history of pottery, I would understand that William de Morgan played a not insignificant role during the Arts and Crafts Movement in England by reviving the art (and craft) of “lustreware” – a practice whereby a crockery objet d’art is finished with a metallic, iridescent glaze. It seems that Mr. De Morgan was really good at this. He was also really good at writing and Mrs. De Morgan has, kindly, placed several of her husband’s better-known novels on the bookshelf behind him.

Even though he is the subject of the work, I should be loath to discuss the artist’s husband more than the artist herself. Evelyn de Morgan was a pioneer whose entrance into the almost exclusively masculine world of professional art was only made possible by her remarkable ability and tireless work ethic. To be perfectly honest, if I was attempting to present the stunning talent of this woman, this is one of the last paintings I would choose as it does a far better job of showcasing her love for her husband than her competence as a painter.

I trust you see my point now. I think it is pretty clear that the snarky, cheeky attitude with which I originally approached this work has been overtaken and boarded by piratical sentiments of admiration, curiosity and respect. What a woman! What a man! What a marriage! What a vase!

The price of this change of heart? Humour. That’s the price. I am so terribly sorry.