In recent months, tensions with indigenous peoples have spiked across Canada as energy companies seek to construct projects on and through indigenous lands. Both TransCanada and Kinder Morgan are attempting to build their Coastal GasLink pipeline and the Trans Mountain pipeline.

First Nations have been emboldened by this summer’s Supreme Court of Canada William decision, which recognized the aboriginal title of the Tsilhqot’in nation to 1,750 sq km of their land in central British Columbia.

While the ruling did not defer outright ownership, but the right of use and stewardship of land while reaping its economic benefits. As a ruling on the federal level, it affects all “un-ceded” territory in Canada – lands never claimed through war or by treaty.

This landmark ruling by the supreme court has created a precedent that is particularly worrying for large scale resource extraction infrastructure investments across Canada.

However, with the Kinder Morgan and Trans-Canada pipelines, there has been an aggressive acceleration in the development of their projects likely in attempt to increase the scale of the investments in order to forcefully influence policies determining the reality of aboriginal title

In an interview with The Guardian, Gordon Christie, a scholar of indigenous law at the University of British Columbia said,

Unlike the rest of the country – where relationships between indigenous groups and the state are governed by treaties – few indigenous nations in British Columbia ever signed deals with colonial authorities, meaning the federal government still operates in a vacuum of authority on their lands. What I see is a long history of the Canadian government doing its best to avoid acknowledging the existence of other systems of government. The Crown has itself acknowledged that the way it gets authority over territory is through the making of a treaty. So, this is their problem.

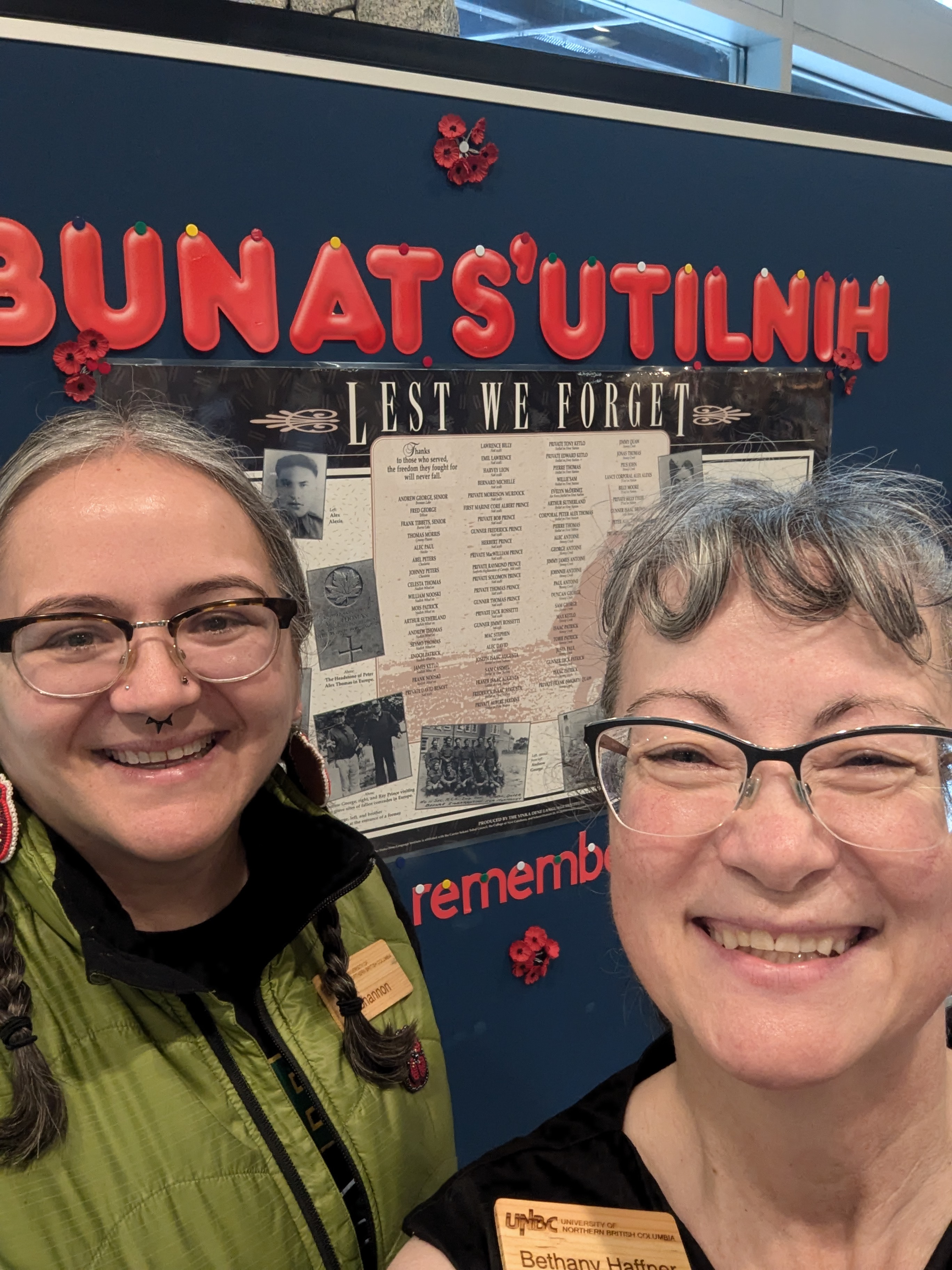

Under ‘Anuc niwh’it’en (Wet’suwet’en law and system of government) all five hereditary chiefs of the five clans of the Wet’Suwet’en nation are openly opposed to the TransCanada liquefied natural gas pipeline that will be built through their territory.

The Wet’suwet’en, which is made up of five clans, never signed a treaty ceding their land to the government of Canada and they retain control of who enters it.

The structure of the Wet’Suwet’en traditional system of government is built around the decisions of their hereditary chiefs who were never consulted, rather than their elected municipal leaders who were consulted instead. In the 1997 landmark case, the Delgamuukw v British Columbia case, which covers part of the Wet’suwet’en territory, previously found that

the We’suwet’en people as represented by their hereditary leaders retained indigenous rights to their historical territory, and these were not to be “extinguished” by lack of a treaty.

However, in a reversal of precedent the RCMP have obtained a court injunction to forcibly clear an access point for construction crews to move into the territory. Currently police have set up an “exclusionary zone” to prevent access to the area – and have told those trying to access the roads they face arrest if they attempt to enter. With residents being barred from entering their traditional homes.

The RCMP’s actions granted by this court injunction is a siege on violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, is an extension of the genocide that the Wet’Suwet’en and have survived since contact, and a siege on a peaceful demonstration of free speech regarding resource projects they say they never consented to.

The past two years have been a turbulent time for indigenous rights. Last year, in February,

a farmer named Gerald Stanley was acquitted by an all-white jury in the murder of Colten Boushie, a young Cree man.