Picture this. You are biking up a steep road in the rain, with a heavy backpack, and you’re chugging along at 8 km/h. You didn’t sleep great last night, had a breakfast of Fruit Loops, and you’re struggling to keep your bike steady. There’s a vertical curb to the right, and you’re trying to get around a storm drain in a lane the same width as your washing machine. Cars, trucks, and buses are passing you at over 100 km/h and are spraying you with a mix of gravel, dirt and water. Sound like a nightmare?

Bike logo painted onto the curb and storm drain

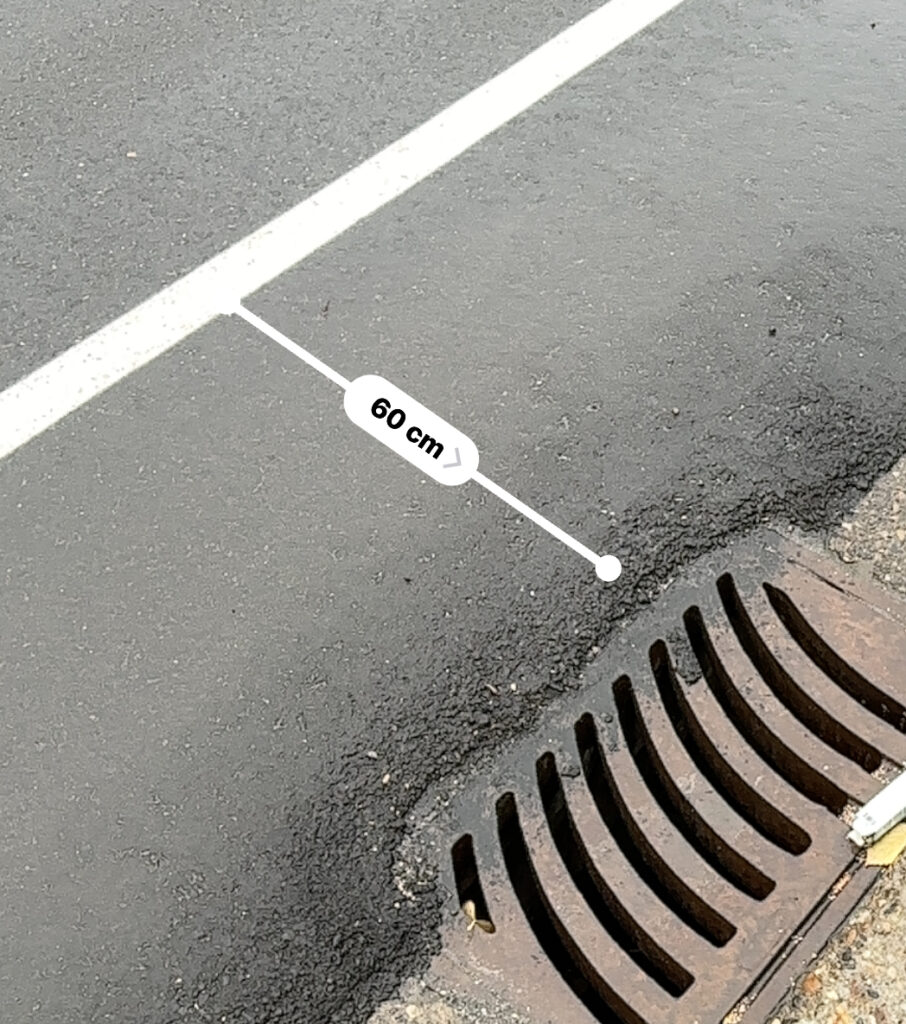

This is the reality for anyone who wants to bike up University Way in the designated bike lane. The average width of the paved section of the lane is around 85 to 90 cm, and this is reduced to 60 cm when you need to get around a storm drain. This lane, which should be a safe space for cyclists, is no more than an afterthought, wedged between fast-moving traffic and a vertical curb that makes any sudden swerve impossible. This lane is so thin, that in some places, the bike symbol is painted onto the curb and even the storm drain.

Measurements of the widest and thinnest part of the University Way bike lane

For anyone unfamiliar with cycling infrastructure standards, this might not immediately sound like a crisis. But according to BC’s Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, a paved bike lane should be at least 1.5 meters wide (BC TAC 2019). The university bike lane falls far below that standard — sometimes by nearly a meter. If you treat University Way as a freeway and drive over 100 km/h (which many drivers do), the lane is almost 3 meters too thin in some spots. A lane below 90 cm in width doesn’t just fail to meet the minimum: it’s unsafe by design. It’s hard enough to navigate in good conditions, but add in bad weather, poor visibility, or a distracted driver, and it becomes a death trap. Having two car lanes up the hill turns this road into a highway, with people driving above the speed limit on the right, and way above the limit on the left to pass. To top it all off, the two car lanes near the top merge into one, and I’ve seen cars failing to merge fast enough, forcing them into the bike lane to get enough room. Hearing all this, you might be thinking, “Why don’t you just bike on the sidewalk?”. Well, according to BC cycling laws, that’s illegal.

Foothills Boulevard, from Moore’s Meadow to University Way, is an example of a good (partial) bike lane. It is wide enough that you could almost be passed by another cyclist. Unfortunately, it’s a half-hearted attempt. Past Moore’s Meadow to Otway Road, the lane becomes the same width as the one up University Way. If you’re going uphill from the River on Foothills, the lane almost disappears when going past Rolling Mix Concrete. Why is there a trend of bike lanes getting thinner when cyclists need to go slowly uphill?

Bike lane from Moore’s Meadow to the bottom of University Way

I see only two solutions: either make the lane wider, add a barrier, and remove a car lane; or move the sidewalk and the curb inwards to free up space. The first option would be the easiest, and the road merges into one lane at the top anyway. But of course, I see this causing many complaints from the people who will lose a couple seconds of time, after they’ve spent 10 minutes in the Starbucks drive thru.

I doubt either of these solutions will even be considered unless a cyclist gets seriously injured or killed when using the lane. But why does it have to come to that? Why do we allow our most vulnerable road users to risk their safety daily just to get to school, work, or home? This shouldn’t be the price of choosing a sustainable and active mode of transportation. Cities have the power and responsibility to protect all road users, especially the most vulnerable. Until we recognize the value of cyclists and commit to proper infrastructure, the reality remains that choosing to bike to UNBC is often choosing to risk your life. It’s time to make cycling safe for everyone, not just those willing to ride on the edge.